Adding accessory dwelling units to the close to half a million single-family properties in Los Angeles would go a long way toward making affordable housing available, improving the environment of single-family home neighborhoods, and increasing equity in the residential landscape.

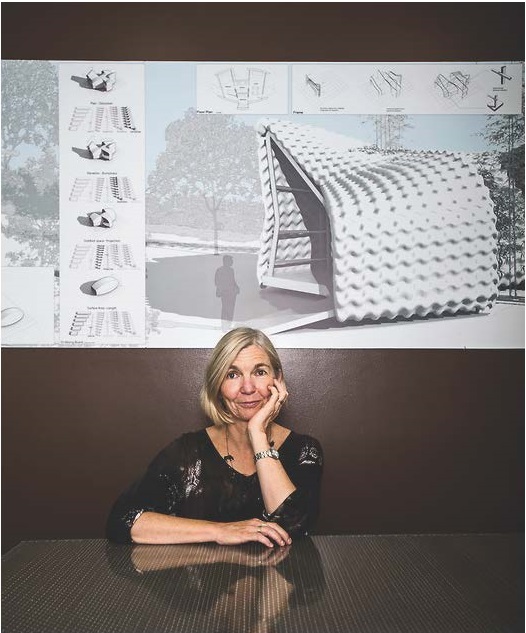

And it’s a solution that many have already turned to in some communities. That’s what Dana Cuff and her team found. Cuff is a professor of architecture at UCLA and director of CityLAB, a think tank concerned with spatial justice, urban design, and architecture.

ADU Magazine connects with Dana to discuss how she became interested in the ADU space and the many opportunities for providing affordable, equitable housing and the benefit to the environment.

Following find selected highlights and excerpts of that Question & Answer Session.

We estimate there are 8 million single-family properties in the state of California. That’s a little bit of a hard number to get your hands on. But we could double the density of those single-family properties. We would have a better environmental equation, and we would have more housing, which inherently would make housing more affordable if we had a bigger supply.

Cuff: We started off working in ADUs, primarily because we were trying to encourage market-based housing production that might be more likely to be affordable and that would stabilize neighborhoods. So, we really had a kind of social agenda behind what we were doing. And for me, as an architecture professor, I also saw ADUs as a way for young architects to become engaged in practices in ways that would be really exciting for them. And there aren’t that many opportunities these days with small projects for young architects.

Being from Los Angeles, we face both a housing crisis and an environmental crisis, and a lot of that’s produced by cars. So, the idea that we might be able to densify the 460,000 single-family properties in the city of LA…

We estimate there are 8 million single-family properties in the state of California. That’s a little bit of a hard number to get your hands on. But we could double the density of those single-family properties. We would have a better environmental equation, and we would have more housing, which inherently would make housing more affordable if we had a bigger supply.

And particularly for me, as an architect, the design of smaller units is something that I think is a really important challenge. When we as architects first started designing houses that were kind of mass-produced. Let’s say after that era of manor houses, but in the Second World War when we started making housing for the middle class, they were 700 square feet. You know, Levitt townhouses were 800 square feet, and it was a perfectly reasonable housing size. And it’s just mushroomed since then, and it’s time for those sizes to come back down. If they’re well-designed, I think people will find it’s very livable. The tiny house movement is one extreme, somewhere in between that and the 3,000 square foot suburban house, which I think of as a house kind of on steroids. There’s bound to be some great housing that could be made available and more affordable for Californians.

Cuff: I wrote a book about housing, especially social housing or public housing in Los Angeles in like the year 2000. I’d been working on public housing for maybe a decade before that and trying to figure out why is it that we can’t make more social housing that would increase equity in our residential landscape? And how might architects get involved in that?

So, I was an architecture professor, and I have a PhD in architecture, so I don’t practice architecture. I study it and teach it. And now I have CityLab, which is a kind of design research center. So, it was really always trying to find ways that what I think is really architecture’s potential contribution to the production of low-cost and affordable housing might be unleashed.

And we ran a little competition for young architects and planners and real estate students and recent graduates, and found one of the teams suggested, in 2006 or 2007, and found that a lot of communities didn’t want a big condominium development here, or a multifamily housing development, but they all already had and wanted more granny flats. So then we did a field survey. We drove around to see because nobody knows how many informal granny flats already exist. You kind of suspect maybe at the neighbor’s when there’s a window in their garage that’s got curtains on it, somebody’s living there, but you don’t really know.

But we estimated that in some neighborhoods in Los Angeles, as many as two-thirds of the lots already had what some people call “illegal,” but maybe it’s better called “informal” ADUs.

If people are doing this in spite of the fact that they can’t get a building permit, this must be a solution that’s really working for people. So, we built a kind of homegrown solution, and tried to then turn it into something that we could really investigate. And in the end, we did 10 years of research, coauthoring the state legislation on ADUs. So it’s a really great story, from start to finish.

Cuff: The beauty of AB 2299 or SB 1069, the two first enabling bills, is that they are continuing to evolve. And when I give lectures about it, now, the students in the audience say, why did you just say doubling the density? Why couldn’t we triple or quadruple it? And now, you can triple, you can have two units if one of them is a JADU (junior ADU). So, the whole conversation around sharing your single-family property, I think, is really changing in a very positive way.

Cuff: Oh, yeah, CityLab. And with Richard Bloom’s office (D-Santa Monica). He’s our congressman. And he asked me to help him organize an affordable housing brain trust, and it was out of that that my colleague, Jane Blumenfeld, who I worked with, former person from the LA Planning Department, she and I did the authoring of the bill in concert with Richard Bloom’s legislative analyst. And then we found our colleagues, some women I knew, it was all women.

Housing tends to be one of the subfields in architecture planning and real estate that women have been very active in. And you know, maybe that’s because of the gendered association of housing. I mean, those are just old norms that seemed to persist. In any case, it was very productive here because a couple of women’s scholars that I knew up at Berkeley who have long worked on ADUs and secondary units were coauthoring legislation with their Senator Wieckowski (D-Fremont), and so we married the two bills.

Cuff: To me, there are a few real challenges, and we’re starting to work our way through them. One is financing; that’s a major one for homeowners. Like, what are the mechanisms to build these? And then I guess I’d say the other is the construction process. Like many, many, many homeowners don’t want to be project managers – have a construction job, because they have full-time jobs already.

So the third struggle is the one of those new entrepreneurs trying to fill those spaces. How to build economically and with certain kinds of financing in ways that they can manage construction, and still engage the homeowner in the process. …People have created dashboards so that people can evaluate whether their lot is amenable to a secondary unit – do they have enough space, what would it mean in terms of the zoning and setbacks, and all that. Those have been pretty successful. Then there’s the next level, which is a dashboard plus a kind of graduated set of services. So, for $99, give us your address, and we’ll determine with how big of an ADU you might be able to have, and then for $1,000, we’ll give you plans. Then people have certainty built into it, which is not something that is readily available in construction.

As a homeowner who does maybe only have one project in their lives, like maybe a remodel plus an ADU, you need a trusted expert to work with. So, these new kinds of firms are trying to create that kind of business model to offer to homeowners. And they’re really interesting, they range from little local contractors who say on the side of their truck “ADUs R Us” to people who are doing prefab buildings who offer three different models and will take it from construction start to finish.

When you look closely, they haven’t built very many of those. And venture capital getting into it is something that’s kind of interesting. A few different firms are trying that.

So there are all kinds of interesting barriers to making this easier. The legislation does a great job at that. But I think the construction process and the financing are the areas where most innovation is being focused with moderate levels of success.

Cuff: Well, for sure, those are the opportunities too. I’m interested in the full spectrum of opportunities – from homeowners to builders to renters. All of those people have opportunities here. I think we still need advocacy. For, for instance, like the Neighbors for more Neighbors model, that’s the Minneapolis group, and to me, that’s a really important opportunity for advocacy for more affordable units and more units per site.

And as we build that, we overcome some of the resistance that we have as natural in transforming from one house per lot to a much more robust kind of neighborhood life. And people have to get adjusted to that. But that’s been a form of segregation, as we now know, and discrimination against people of color, particularly African Americans. So, the single-family zone itself has prevented people, and it was intended to prevent people of color from owning property. We have to help undo that harm in some way, and I think opening our ideas and imaginations to really great ways of living more densely and compactly in communities is an important part of that.

I think the opportunities for homeowners ought to be expanded. Also, so that it shouldn’t be hard for them. As they see their neighbors doing it, a lot of people get interested. It’s kind of understandable that you want to see how it works for somebody before you try it. In some ways, that’s been the problem with bank lending is that they are also risk-averse, so they want to see how it’s going.

But I think we ought to be making it easier for homeowners, and some of these new forms of home delivery really are important in that regard. All the prefab stuff is really interesting. People kind of have a negative attitude about that, like, maybe it’s going to look like it’s factory-made, but you can’t even tell anymore. And that really helps with the construction process, most of it happens off-site, so then homeowners aren’t so disrupted.

And then I think, opportunities for architects and builders are definitely growing in this. Like, almost every small architecture firm I know has a little ADU. And that’s a really wonderful way to help small businesses in the state and the same with small contractors, you know, people just getting started. For the last 30 years, there’s been a kind of merging towards larger and larger organizations in the construction industry, them dominating more of the dollars in the building industry. So to bring it back to the small folks is really an important opportunity that the ADU market is creating.

Cuff: We should be looking at some lots, maybe corner lots and alley lots and large lots, as being able to sponsor even more secondary units. I think another future for ADU is that it be able to be subdivided and become an owner-occupied unit, not a rental unit. So that’s an important piece.

In Japan, you can sell any property that somebody is willing to build up. Like, if you’re willing to build on a 10 foot by 10 foot area, you can have it for a house, and you see some really remarkable tiny houses. And for me, that’s a really exciting direction to be heading. But some neighborhoods should be trying these things so that other neighborhoods can see that it’s not threatening, but could be kind of exciting, and it could be environmentally very smart.

I think there’s a lot of development in the building technologies, everybody’s trying to figure that out, like 3D printed buildings, prefabs, modular, all of that. We haven’t really hit the sweet spot. Although I’d say prefab has come pretty close now, but it’s just that the costs aren’t coming down with it. So, looking for more economical building technologies is important.

And the last one, I’d say, is one that I’ve been working on with colleagues in Australia, and it’s called Right Sizing Houses. That is a little bit related to the junior ADU idea. In the bigger, older housing stock, but also probably the bigger housing stock of the, say 90s, you can carve a house interior differently, and make multiple units there so that each one has a nicer size and fitting to current households.

The most common household in America today is a single person, and it’s been that way for some time. I think the average size is like 2.3 people or something. But more single person households exists than any other type.

Cuff: Yeah. Why are we making all these suburban things or why have we been? And it’s because of an idea about exchange value. Like people think, well, if I don’t have three bedrooms and three baths, and a grand room and whatever else goes into those, I won’t be able to sell it, it won’t increase in value. But that’s a myth, right? I mean, we can write a new one and some developers are doing that now, creating extended family production houses, for instance.

So, I think there’s so many ways in which secondary units are the beginning of really just much more innovative and responsive housing for California in particular.

Images by: David Zentz

Mid Century Mod ADU in Sunny San Diego 380 sq.ft. Private Modern Attached One Bedroom…

Contemporary Attached Cottage in Palo Alto, CA 227 sq.ft. Cozy Contemporary Attached ADU This cozy…

Cash-Out Refinance What it is: From the point that a person buys a house, they will…

Finding ADU Software to Build the Perfect ADU The accessory dwelling unit market has blossomed…

Renovation Loan What it is: A renovation loan allows homeowners to get a loan for their…

The Ins and Outs of ADU Financing Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) have been gaining in…